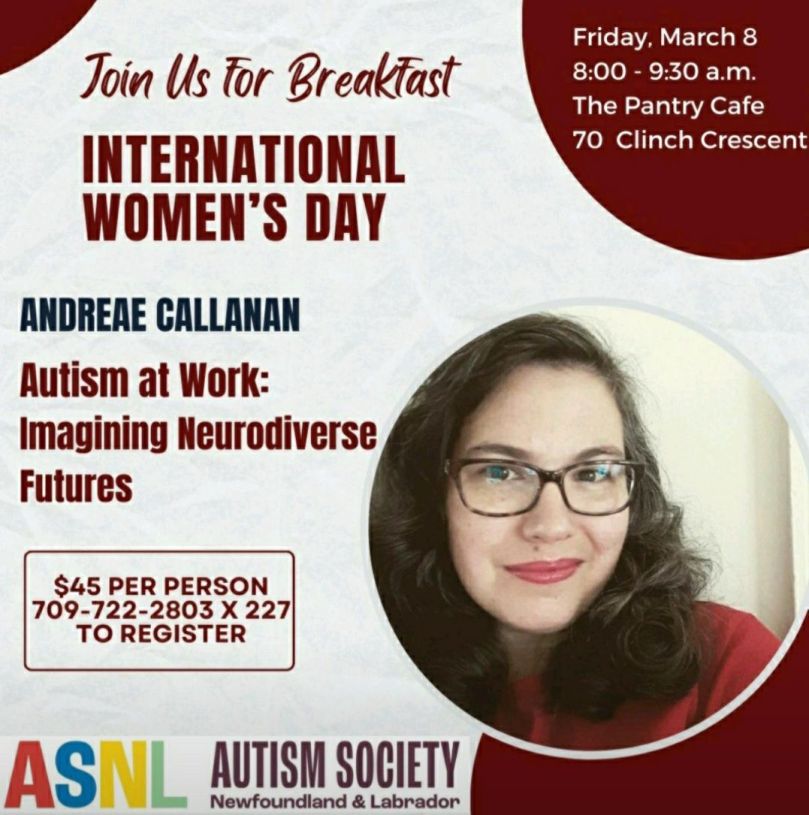

This talk was originally written for the Autism Society of Newfoundland and Labrador‘s International Women’s Day breakfast, which had been scheduled for March 8th; a snowstorm meant that ASNL had to reschedule the event for March 20th.

I had a lovely time speaking, and ate a lovely breakfast — if you’re local and haven’t been to The Pantry yet, what are you waiting for?

The attendees were an absolutely stellar crowd, and I truly couldn’t have asked for a warmer and more welcoming group. I promised I’d post my talk here for folks to re-read and share, so here we go — minus some of my impromptu bits, which of course will be lost to memory.

Many thanks to ASNL for inviting me, and for providing the resources, skills, and sense of belonging that are so crucial for autistic people of all ages.

One more note: since the people in the room could see me — and since I knew many of them already — I didn’t make any kind of positionality statement. Folks reading this might be meeting me for the first time, so I should probably mention that this talk represents my experiences as a white, middle-aged, feminine-coded, cisgender, Canadian-born anglophone woman who is middle-class-passing but who has experience of both child and adult poverty, and whose disabilities are relatively inconspicuous in most contexts.

Autism at Work: Imagining Neurodiverse Futures

Thank you for such a lovely introduction, thank you all for coming out, and thank you ASNL for inviting me to speak – and for rescheduling the event when nature had other plans for us. It’s worth noting that this week is Neurodiversity Celebration Week, which I suppose, is also fitting. So: happy Neurodiversity Celebration Week, and happy belated International Women’s Day.

The first International Women’s Day was a bold proletarian project under the leadership of Marxist theorist Clara Zetkin. It was held on March 19th, 1911, as a socialist initiative to demand equal voting rights and to rally for labor legislation for working-class women, social assistance for mothers and children, fair treatment of single mothers, provision of childcare, free school meals, and international solidarity.

Over a century later, we’re still working on many of these things. But as a bit of an old socialist initiative myself, I have a soft spot for the day.

The theme for this year’s International Women’s Day proposed by internationalwomensday.com – which, it goes without saying, did not exist in Zetkin’s time – was “Inspire inclusion.”

If I were facilitating a poetry workshop, and one of the participants submitted a poem with the line “inspire inclusion” in it, I’d pass that back with a big question mark.

Being autistic, I tend to struggle with abstract concepts. “Inspire inclusion” is two abstract concepts smashed together. Inspire who? To include whom? In what?

“Inspire inclusion” isn’t the same as “legislate equity.” Being included isn’t the same as being respected as an equal. To me, “inclusion” feels closer to “tolerance” than it does to “admiration.” Then again, that might be because as a middle-aged autistic homebody introvert, my desire to be included in most things is pretty darn low.

Many a researcher has insisted that autistic people don’t “get” irony, but I assure you that I do detect, loud and clear, the irony of “Inspire inclusion” inspiring me as an autistic person to point out how non-inclusive “Inspire inclusion” is.

I’ve titled this talk “Autism at work: Imagining Neurodiverse Futures.” That first part – Autism at work – has a bit of a double meaning. I’m talking about my experiences and lessons learned as an autistic person in the workplace. But I’m also talking about how autism is constantly at work in everything I do – in my decisions, in my reactions, in my interpretations of what other people say, in my ideas and how I communicate them.

The Buckland Review of Autism Employment: report and recommendations, which came out in the UK at the end of February, defines autism as:

a lifelong developmental condition that can occur at all levels of ability, across all social classes and ethnicities. It is a spectrum condition and often occurs in combination with other conditions, including ADHD, learning disability, dyslexia, dyspraxia, dyscalculia, speech and language difficulties and mental health conditions. Most autistic people see autism as a part of their identity that cannot and should not be separated from other aspects of who they are.

I think that’s a pretty good definition – it’s value-neutral, it highlights co-occurring conditions (what I call “subscribing to the neurodivergence bundle”), and it talks about autism as an identity, which is something a lot of autistic people relate to.

But it doesn’t get at what it feels like to be autistic.

For that, my go-to definition comes from a researcher named Elizabeth Fein, at Duquesne University in the US, who describes autism as:

more like color than like color-blindness – it’s a thing that happens between sensing bodies and sensuous worlds … I have come to think of [autism] as a mode of engagement with the stuff of the world – a way of being with one’s surroundings. In particular, it is a form of permeability, of deep existential vulnerability, to the order of things around us…

For me, Fein’s description captures what is so thrilling, so overwhelming, and at times so agonizing about being autistic. I often feel like I’m plugged into a thousand outlets at once, with data and sensations and images and sounds coursing between me and the room I’m in. When I leave my house and go to work, I’m plugged in to my office’s electric lights, the meeting happening in the next room, the potted plants, the feel of the carpet under my shoes, the materials and the cut of the clothes I’m wearing, the hum of my laptop charger, the smell of used coffee grounds stewing in the bin… and that’s before I’ve even spoken to another human.

So far this lifetime I’ve worked as – in no particular order – a waitress, a barista, a gelato-scooper, a caterer, a workshop facilitator, a salesperson at an upscale toy store, a newsletter coordinator, a writer, a touring puppeteer, a researcher, an editor, an indexer, an administrative assistant, a bookings coordinator at a historic folk music venue, a web content provider, a website builder, a research assistant, a university creative writing instructor, a quality assurance specialist, a theatre festival outreach coordinator, a community development worker, and a muffin baker pulling the overnight shift alone in a vegetarian restaurant.

Some of these jobs were unmitigated disasters. Many of them ended in burnout that took months and even years to recover from. Some were absolute blasts! All of them were defined and mediated by my autism.

When I’m able to use my powers of pattern recognition to anticipate a dozen potential end results of an initiative, that’s autism at work. When my brain’s resistance to ranking information into neat hierarchies of what’s important and what isn’t leads me to include details in a report that other people might skip over, prompting colleagues to exclaim, “oh! I wouldn’t have thought of that!” that’s autism at work. When I analyse the living daylights out of a seemingly innocuous theme like “inspire inclusion” to show how it actually excludes some divergent communication styles, that’s autism at work.

And when I go into shutdown mode at a colleague’s retirement lunch because we’re at a loud restaurant, and all the food is salty and gluey and the room has terrible acoustics and is playing awful music while different TV monitors in different corners of the space are tuned to different channels, and everyone’s chairs are scraping, and everybody’s talking at the same time, and my seat is at the end of the table next to the bathroom so the food smells are mixing with the air freshener smells and now my pasta tastes like warm industrial cleaner… that’s autism at work, too.

And if you want to benefit from the former, you have to be willing to accommodate the latter.

Autistic workplace accommodations aren’t quite the same as ramps or rails or automatic doors – they’re not always material or tangible. An employer can’t easily apply a dollar figure to them. And they’re not universal, because autism looks different from person to person. One autistic worker might benefit from flexible deadlines, while another (me) will totally flounder if she knows her deadlines aren’t set in stone.

The jobs where I’ve thrived have been ones where I’ve been given crystal clear instructions and then been left on my own to follow them – where I’ve been trusted to complete the task as defined, and where I could trust my higher-ups to answer my questions without being judgmental or dismissive.

Other autistic people might work best in rooms with specific lighting or sound levels, or they might need to move around from room to room for different tasks. They might need to wear headphones or sunglasses. They might need an emotional support stuffie. They might need to work from home. They might need to not work from home. They might need regular check-ins, or they might hate regular check-ins. They might need more time to recover from a labour-intensive task than other workers, and they might prefer to celebrate a job well done by sitting quietly at home rather than by hitting happy hour at the pub (although many of us are pub aficionados, too).

It’s easy to forget, in 2024, that when women first elbowed our way into workplaces that had once been the exclusive domains of men (and I acknowledge here, of course, that women have always worked outside the home – just not necessarily in spaces where men were the norm), we needed accommodations. Some buildings needed women’s washrooms, for one thing. Those of us who move through the world as cisgender women would do well to remember this when our trans and nonbinary peers share their frustrations and fears around safety in washrooms. We didn’t always have a place to pee, either.*

Patriarchy being what it is, women’s presence in male-dominated spaces meant that we needed to implement sexual harassment policies – if not to prevent unwelcomed sexual attention, then to at least discipline the perpetrators. These policies now protect (in theory, at least) workers of all genders from harassment.

Maternity leave is another accommodation we probably take for granted, but it too came about as a way to acknowledge the realities of women’s lives while also allowing us to advance our careers – and, of course, maternity leave has been expanded into parental leave for new parents of all genders, and applies to adoptive families as well as birthing ones.

You’ll see a common thread here, and it’s this: the accommodations put in place to allow women to succeed in the workplace actually benefit everyone.

The same can be said, I believe, of the accommodations many autistic people require.

If you know me, you’ll probably have heard me say (at least once) that nobody ever suffers from instructions being too clear.

If you mean “all staff are expected to attend the festive holiday luncheon on December 18th,” then don’t say “all staff are invited to attend the festive holiday luncheon on December 18th.” Those are two different things – and actually, neither one of them conveys that all staff are required to attend the festive holiday luncheon, and will be ill spoken of if they don’t. So, if that’s what you mean, you’d better just come out and say it.

I think we’d all be concerned if we saw, in the washroom of a fast-food establishment, a note detailing that team members are invited to wash their hands before returning to the kitchen.

If you don’t know how to communicate in an autism-friendly way, hire an autistic person as a consultant (and pay them like you would pay any other expert).

If you don’t know what accommodations an autistic employee or colleague needs, get to know them.

That’s the first part of my title. What about the second bit? Imagining neurodiverse futures. “Neurodiversity” is the brain equivalent of “biodiversity,” meaning many different sorts of brains functioning together in an ecosystem. The group in this room is a neurodiverse group: it includes (presumably) people who are neurologically “typical” – that is, whose brains show no discernable divergence from the medical norm. And we have people who are autistic, and I’m sure I’m not the only person here with ADHD, and for all I know there could be people here with dyslexia, or brain injuries, or whose neurological profile has been permanently altered by decades of transcendental meditation or by one weekend of too much LSD or who knows what else. Neurodivergence – that is, being neurologically not typical – covers a lot of different kinds of brains.

And we need each and every one of them.

We all know that biodiversity is crucial. So is neurodiversity. And we have never needed it more than we need it right now.

We are living through a time of massive turmoil and upheaval. Ecological catastrophe at a global scale, widespread economic calamity, the disabling fallout of the ongoing COVID pandemic, the death throes of cis-hetero-patriarchal capitalist imperialism… there’s a lot going on.

Neurotypical approaches haven’t been much good in sorting it out, or in preparing us for possible outcomes. It could be argued that neurotypical failure to see patterns and connections between us humans and, to return to Elizabeth Fein’s words, the stuff of the world is how we ended up in this constellation of messes in the first place.

If there has ever been a time for new ways of looking at things, new approaches to problem solving, new and weird and unorthodox ways of harnessing different modes of cognition, it’s now. Our future relies on us finding strength in our diversity, and on allowing those of us who see the world a little differently to have a go at fixing what’s wrong.

I’m going to finish off here by coming back to this year’s theme: Inspire inclusion. One thing I’ve been reflecting on lately is just how many autistic people are drawn to social justice movements – like the labour movements that got us washrooms and harassment protection and parental leave, and like the proletarian suffrage and solidarity movement that got us International Women’s Day in the first place.

Let me offer you one more definition of autism. This one is from writer and editor Maura Campbell, who writes,

Autism is a lifelong condition often characterized by:

- an inability to bullshit

- a pathological need for fairness

- a compulsion to help others

- an inexplicable need to expose hypocrisy

- an excessive tendency to let other people be

There is no known cure.

I know not all autistic people are Greta Thunbergs – we have to put up with our share of Elon Musks, too. And I, for one, can bullshit with the best of them. But Campbell’s point stands that autistic people tend to be a little bit allergic to social norms – it’s not that we don’t understand them so much as that we just don’t really vibe with them. It’s hard to invest in the norms of a society that doesn’t invest in you. I’ve known so many autistic people in my life who feel a deep drive towards justice, who have a razor-sharp ability to see through doublespeak and double standards, and who share a commitment to using our gifts to help repair the world. For many of us, being included in an unjust system is nothing to celebrate, and certainly nothing to strive for. We’d rather remake the systems into something we can be proud to be a part of.

I suppose many people might listen to me say this and ask, “why on earth would I even want to include autistic people, with all their bluntness and resistance and needs and general apple-cart-upsetting ways?”

To which I’d ask: can you really afford not to?

So let me propose a slight edit to this year’s International Women’s Day theme. Let’s not settle for “Inspire inclusion.” Let’s demand inclusion, and inspire one another to work for change.

Thank you.

*I should have noted here that, of course, being a cisgender person doesn’t guarantee anyone a place to pee — plenty of people who use wheelchairs and other mobility devices are still limited in terms of where they can go because many buildings aren’t required to have accessible washrooms (or any access features whatsoever). My apologies for having left this important fact out!